Brickwork of Montrose Park

New Jersey had robust clay-based industries, including ceramic, brick and architectural terra cotta throughout its history. Production centered mainly in the “clay belt” that runs diagonally across the state between Perth Amboy in the east and Trenton in the west. Clay products and bricks were manufactured on a large scale in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Montrose Park offers a look at a variety of bricks and how their variation can transform architecture.

Basic red bricks laid in white mortar are a “classic” American material, used since colonial times for the finest houses, civic and religious buildings, and commercial buildings. The “early American” past was recalled in the popularity of the Colonial Revival style of the period from the 1910s through the 1940s. Both clapboard and brick were favorites for Colonial Revival houses.

224 Warwick Avenue, a classic 20th century brick Colonial Revival style house. Recalling but not directly imitating Georgian houses of the 18th century, it incorporates symmetry in the main block and a decorative center entry with sidelights and fanlight. Photograph by Janet W. Foster, May 2017.

The paired gables on the front of this house built about 1920 emphasize a symmetrical façade that is anything but classical or colonial. In addition to the fireproof tile roof, the house features a honey-toned “iron-spotted brick” – an unusual brick made with bits of iron mixed into the clay. When the brick is fired, the iron causes “blooms” of warm, rusty color. Spotted brick was intended to give a more hand-crafted, irregular appearance to an industrially produced product.

Iron-spotted brick used at 245 Montrose. Photograph by Janet W. Foster, May 2017.

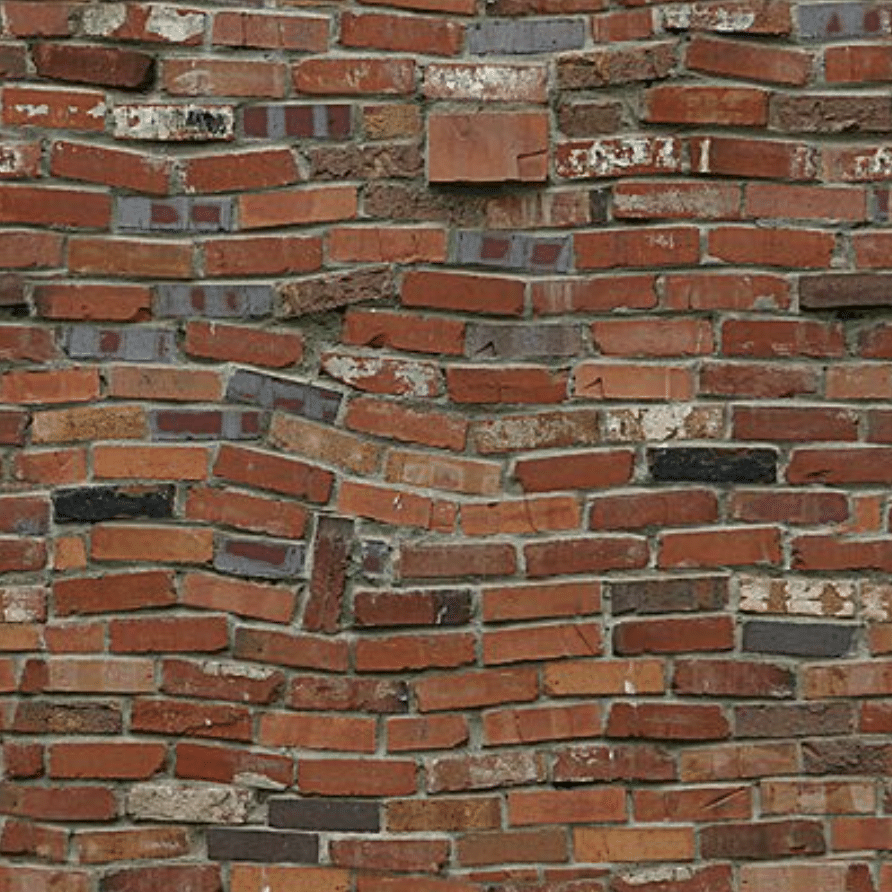

In the 1920’s interest in historical architecture was not just about picking and choosing elements from the past to recombine in a modern building, but the use of industrially produced materials to mimic handmade things. The brick exterior walls at adjacent houses at 260 and 270 Montrose Avenue are industrially produced, but the hard-edged look is softened by tumbling the brick to give it an aged appearance. The way the bricks are laid, with intentional wavering joint lines and an irregular surface, emphasizes the “craft” of brickwork. This is sometimes called “drunken brickwork” – for obvious reasons – or “Hollywood” brickwork because of its fantastic nature, and its appearance in the 1920s, along with Hollywood as a prime creator of illusion and fantasy. It is, in fact, very difficult to execute, and although the look is “thrown together” it is time consuming, and therefore, expensive, to do.

Example of “drunken brickwork”. Photo from Pinterest; in the pubic domain.

The Romans made bricks with a pronounced long, narrow form that differs from the blocky, rectangular shape that Europeans, and then Americans produced since the 1500s. In the late 19th century “Roman brick” was revived and it had a limited popularity in very high-style buildings. Roman bricks may be seen in Montrose Park on the house at the corner of Turrell and Charlton Avenues. The upper levels of a late 19th century house were destroyed in a fire in the 1960s; the base was re-used for a Modern house. The beautiful honey-hued Roman brick and two surviving Corinthian-style columns hint at the Classical Revival style grandeur of the original residence on this site. The juxtaposition of ancient brick form and modern design is not unique here; Frank Lloyd Wright used Roman brick in several of his early Prairie Style houses.

Roman brick at the Robie House, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, 1909. Photo in the public domain.