Villas and the Suburban Landscape of Montrose Park

In the 18th century, the classical language of architecture was the basis for high-style Western architecture, notably in the Georgian styles of England and its colonies. Classical architecture was about a strict symmetry and order; the dominance of building over landscape, of man over nature.

The Romantic Movement, begun in earnest in the early 19th century, took hold in architecture, art, and literature as a reaction to all the strictures of classicism. One of the first manifestations of Romanticism as a design idea was in the development of domestic landscape that was “picturesque”, or intentionally naturalistic. The concept of “The Picturesque” came to stand for everything Classicism was not: emotional instead of rational; irregular and asymmetrical instead of clipped and symmetrical; buildings integrated into nature instead of dominating the natural world.

“Kindred Spirits”, a painting by Asher B. Durand of 1849, shows a view of the Catskill Mountains as a Romantic landscape, where irregular trees and deep chasms dwarf the human visitors. Durand, who lived much of his life in Maplewood, NJ, was a member of the so-called “Hudson River School”, a group of New York-area artists who painted American landscapes particularly along the Hudson River.

The painting is currently owned by the Crystal Bridges Museum, Bentonville, Arkansas. Image in the public domain.

In the United States, the new vocabulary associated with Romanticism introduced not only the term “Picturesque” but also the term “Villa”. While in the distant past, a villa had meant the house of a Roman citizen of means, in 19th century America it came to mean a large house in a landscaped setting. Tastemaker and author Andrew Jackson Downing did much to promote Romanticism in architecture and design to his countrymen. His popular Cottage Residences of 1842 (reprinted again and again through 1873) defined a villa as “the country house of a person of competence or wealth sufficient to build and maintain it with some taste and elegance.” He further clarified that a villa required the care of “at least three or more servants.”

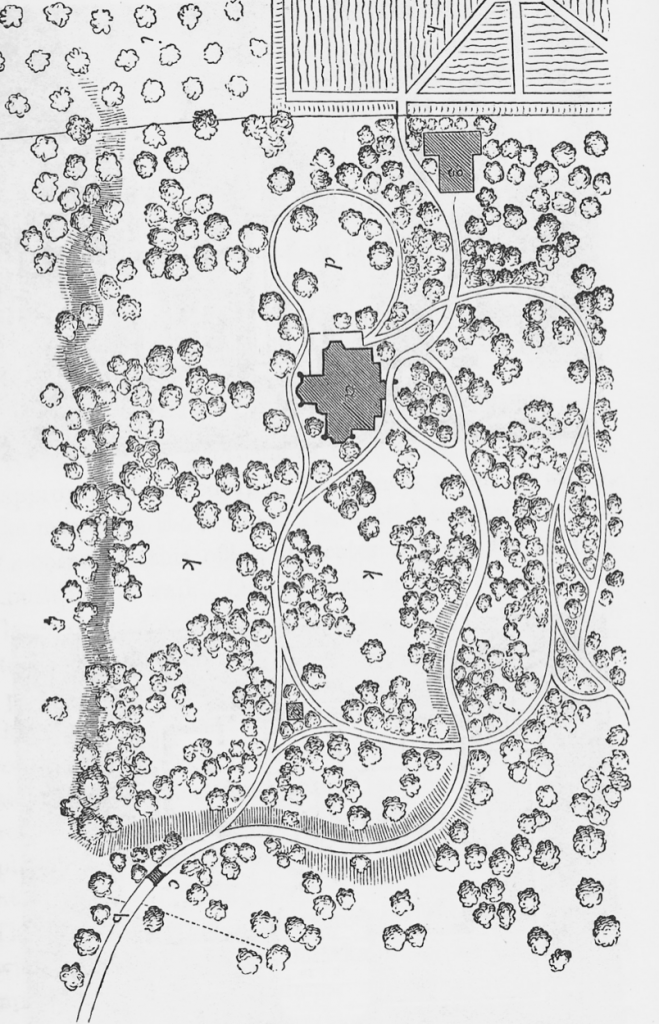

Designs for landscape for country houses or villas, by A.J. Downing, and published in Cottage Residences, 1842. The curvilinear paths and the clustering of trees and shrubs on the property produced a picturesque setting for a house radically different from the clipped hedges and geometric layout of earlier, classically inspired landscapes.

Montrose Park was one of many planned suburbs created following the Civil War, to provide “villa” lots along winding streets for upper-middle class businessmen and their families. The intent of establishing Montrose Park in 1869 was to combine easy access to the city via the nearby train line with the fresh air and open space of the country.

The most commonly used picturesque landscape element in American suburbs of the mid-19th century was the curvilinear street. This was in marked contrast to the grid of American cities, favored since the new street plan for Manhattan was approved in 1811. The gentle hemisphere of Raymond Avenue, Grove Road, and Montrose Avenue gave a semblance of picturesque design to Montrose Park, but its streets had to access rectangular lots, and so they did not veer far from the rectilinear. Contrary to its name, Montrose Park had no actual “park” or common open space, but the restrictive covenants in the deed of Montrose Park property sold by John Vose required large lots, with one house per lot and outbuildings “appropriate for a gentleman’s country residence”. Each homeowner would create their own park-like landscape, and when seen with adjoining properties, the whole would convey the appearance of a continuous manicured landscape dotted with distinctive, individual houses.

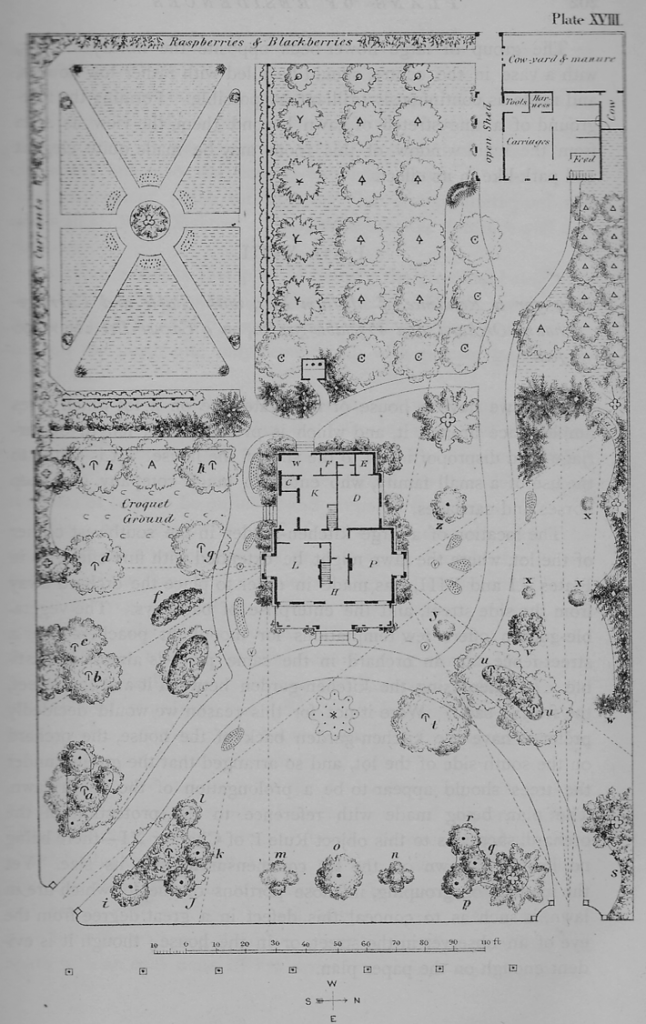

The Art of Beautifying Suburban Home Grounds of Small Extent, by Frank J. Scott, was published in 1873, just as Montrose Park was being developed. The book was dedicated to the memory of A. J. Downing but its focus was no longer the elaborate villa grounds, but a suburban lot of 200 or 300 feet in width. Scott provided plans and directions for maximum use of a property, including vegetable gardens, lawn, and play spaces, often noted as “croquet grounds”.

“Plate XVIII: Plan for Residence of Medium Size, with Stable and Carriage-house, Orchard, and Vegetable-garden, on a Corner Lot 200×300 feet.” Frank J. Scott, The Art of Beautifying Suburban Home Grounds, 1873.

The preservation of this landscape setting is as important as the houses in giving a distinctive character to Montrose Park. Retaining large deciduous trees as well as smaller, ornamental ones in informal arrangement around the property continues a landscaping tradition from the 19th century that works well in the present.